How Do You Paint in Arabic? Exploring the Artistic Oeuvre of Etel Adnan

Encounters: Curator Alia Zaal Lootah on Emirati Artist Connections Across The Ages

Despite its mega-city infrastructure, at the core of Dubai is a village vibe — it is a relatively compact geography where many people know one another or are linked in some way. “Dubai has always been connected to its people and its makers,” says the artist and curator Alia Zaal Lootah. “The early relationship between the rulers and the tradesmen through the ports of Dubai has grown organically over time and created this connection between the people and the government.” This relationship is at the core of the Dubai Collection, a unique initiative that sees local collectors loan their art to create the city’s first institutional collection of modern and contemporary art. “The Dubai Collection creates a collaboration between the state, the collectors, the artists and the public,” Lootah adds. “It’s a beautiful initiative.”

An Interview with Tagreed Darghouth

“We have to share the language that we own with others, and there must be something that the viewer should be highly interested in, because it’s a conversation at the end of the day”.

Expressionism and Engagement. Tagreed Darghouth, Ayman Baalbaki, and the Legacy of Marwan Kassab Bachi

The important Syrian artist Marwan Kassab Bachi (1934 - 2016) moved to Germany in 1957 and spent most of his life in Berlin, studying and then teaching at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste. Unlike many other Arab artists who studied abroad, his work involves a dialogue with the German Expressionist strand of modernism, rather than Cubism derived from Paris, or American forms of Hard-Edge Abstraction.

Memory, Traces & the Passage of Time

Sinuous tire trails cover the foreground of Ali Cherri’s (b. Beirut, 1976) Dust and Other Anxieties (2013). The image, from Abraham Karabajakian’s collection, presents a section of a road. Cherri’s perspective splits the image into three, with marked differences in color and texture. Closest to the viewer is a dark, tire-marked surface. Moving up the image, we notice a flatter, lighter stretch of ground. At the far back, the hazy sky descends onto sandy land; half-hidden by clouds of dust, the fuzzy outline of a monumental statue interrupts the otherwise featureless view.

Density and/or Lightness of Urban Life

Today, over half the world lives in and around a city. By 2045, it will be closer to 70% . As more and more people turn metropolitan, new patterns of urbanity are set to emerge. Creative, dense, contested—cities are alive. They are also hard to decipher, difficult to recuperate within an objective map or explain, minutely, from any singular spot. In this light, the urban artist occupies a special position. She is placed to engage the architectures of our habitations, drawing from the overwhelm of reality and postulating, through aesthetics, the implications of how we live now.

Objects of the Threshold - a liminal reflection

The construct liminal stems from the Latin nouns liminis (or limen) meaning threshold and transire (trans emphasizing the beyond) - to cross over to the other side. Liminality was first used by anthropologists Arnold Van Gennep and later Victor Turner during the 20th century to describe the different stages and the social roles of the rites of passage during rituals (such as marriage or coming-of-age ceremonies). Van Gennep and Turner’s contribution concerning liminality lies in their emphasis on the importance of embracing an in-between, ambiguous, or disorientated state. They argued that these transitional moments are vital for us to move forward as they influence our identity. Contemporary cultural theory, such as Homi Bhabha’s postcolonial perspective in the seminal work The Location of Culture (originally published in 1994), was later greatly influenced by these viewpoints. He defines the liminal as a transitory, mediate “third space of enunciation” that is characterized by uncertainty, hybridity, and potential for cultural change. Cultural liminality is experienced for example when an individual is caught between two cultures after being unsettled or displaced, such as an immigrant experiencing diaspora in a new culture after forcefully having to leave home.

The Desert Picturesque

When considering historical landscape paintings, depicting deserts, palm trees, camels, and large tents in the distance, one might understandably recall images associated with Orientalism. This artistic approach developed from European fascination with cultures and landscapes beyond their own - specifically, those situated to the east of Europe (arguably including northern parts of Africa) - often oversimplified into an imagined collective place known as the Orient. However, Abdulqader Al Rassam’s painting scene from Badia/Baghdad prompts the onlooker to interpret a Middle Eastern landscape that adheres to European landscape painting principles but is neither painted for the European viewer nor portrays the “Orient” as something alien.

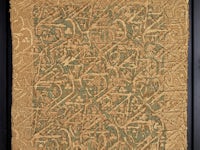

Hurufiyya and the Inspiration of Arabic Letters

The term Hurufiyya comes from huruf, the Arabic for ‘letters’, and refers to a form of painting that combines modernist abstraction with Arabic letters or calligraphy. It was coined by the Lebanese poet and critic Charbel Dagher in his book Huroofiya al-Arabiya: Fan Wa Hawiya (1991), translated into English as Arabic Hurufiyya: Art and Identity (2016).[1]

An Interview with Sarah Al Mehairi

“I think you should absolutely go for what you want to go for, explore themes and concepts that are maybe challenging.”

Dubai Calligraphy Biennale

Calligraphy—from the Greek for beautiful writing —is a form that elevates written language into an aesthetic experience. The medium, however, is more than simply pleasing to the eye. Calligraphy is a people’s expression of harmony, being “a statement about the sum total of [their] cultural and historical heritage.” In this spirit, the Dubai Calligraphy Biennale is a platform that gathers various calligraphic lineages. The event contextualizes penmanship as a carrier of history. The multilingual exhibits are an “opportunity for cultural exchange and understanding.”

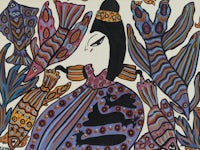

The Diasporic Filipino Artist - Highlights from Filipino Artists in the Dubai Collection

What does it mean to be an artist in, or of, the Filipino diaspora? To live in the Filipino diaspora is to often be in search of rootedness. It is a constant questioning of your identity and how yours traces back to the motherland (or if it should). It is being in constant nostalgia, a perpetual desire to grasp on to something, anything, that will keep you tethered to where you came from.

Hala Khayat in Conversation with Emirati Artist Abdul Qader Al Rais

Time is not the true measure of a person’s success, but rather the achievements made. This is the case for Dubai based painter Abdul Qader Al Rais, who insists on his continuous support for the art scene in the United Arab Emirates. Today he is in the process of building up a studio space which will be also open to host younger Emirati artists he wishes to mentor. Garnering many regional and international awards over five decades of continuous and relentless work, today Al Rais has become one of the most acclaimed and iconic painters of the United Arab Emirates and a pioneer amongst his peers in creating a true distinct Emirati visual identity. With his unique style inspired by the region’s landscapes and the Arabian Desert architecture, his work is identified by lightness and speed.

For love or money: the art of collecting

“Buy what you love.” This catchphrase is often the first piece of advice given to anyone who suggests they want to purchase a work of art. It is usually followed by the equally confounding “don’t buy art to make money”. But how easy is it to get that right? To truly understand what it means when people say, “it should speak to you”? There’s no set criteria or qualifications to become an art collector or patron of the arts. You don’t need to attain a good degree from a top university or complete a foundation course at an arts college. Strong references or evidence of visiting leading museums around the world are not a prerequisite (although it all helps). It is not imperative to declare your financial status either (although efficient auction houses and galleries will do their research). In many ways, it is the most unfettered and liberating position to be in the art world – and the most essential. This is especially true in a new market such as the scene that has emerged in Dubai during the past two decades.

Painting Nothing: An Introduction to Abstract Art in the Middle East

The traditional Western art history books will tell you that the Russian artist Wassily Kandinsky “invented” abstract art—depiction free from representation, focussing instead on elements of form, colour, line, tone, and texture—in around 1910. As with much of the art history canon, this narrative is slowly being unravelled and lesser-known histories of abstraction are being added to the story, such as the contributions of female artists (for example, the Swedish artist Hilma af Klint painted her first abstract work in 1906) and artistic developments in non-Western regions.

Envisioning a New Collecting Institution in the 21st Century: The Beirut Museum of Art, Lebanon

What should a 21st Century museum look like on the inside? As the newly appointed Co-Directors of the Beirut Museum of Art, Juliana Khalaf and myself have almost a carte-blanche to reinvent what this means – an opportunity that comes once in a lifetime for art world professionals. The museum, which is slated to open in 2026, is the first purpose-built museum of its kind for Lebanon, promising to showcase the treasured art collection of the Lebanese Ministry of Culture (which has never been seen before), in addition to focusing on Modern and Contemporary regional art.

Insight: The Dubai Collection

The best examples of art begin conversations. A balance between commercial and didactic activity has always been a strength of Art Dubai’s programming. This is often the case in an emerging market, without established institutional models, and there is so much that has not yet been said–new voices to listen to, trends, movements, styles and influences to identify. It is why Art Dubai has cultivated a culture of discovery, and is a major catalyst in local, regional, and international artistic practice and creative ideologies. It has also consistently been a true connector–leaders and practitioners in the artworld from across continents and diverse art centres come together, often for the first time, and go on to establish impactful partnerships. It has been a unique model for nearly two decades, a space where commercial gallerists, collectors and institutional directors interact, where artists and curators feel at home. Art Dubai has also never only been about a few days in March but extends its reach throughout the year and across the globe.

Modern Iraq: The New Vision Group

A flurry of art groups blossomed in 20th-century Iraq. Following the formation of the country after the First World War and its independence from the British in 1932, a spirit of liberation rippled through the country: it was the dawn of a new age.

The Dubai Collection Announces 279 New Artworks From 19 New Patrons Including 88 Artworks From His Highness Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum

Including the new additions, 406 artworks are now available to view on The Dubai Collection Digital Museum, featuring modern and contemporary artworks by 84 new artists.