How Do You Paint in Arabic? Exploring the Artistic Oeuvre of Etel Adnan

Encounters: Curator Alia Zaal Lootah on Emirati Artist Connections Across The Ages

Despite its mega-city infrastructure, at the core of Dubai is a village vibe — it is a relatively compact geography where many people know one another or are linked in some way. “Dubai has always been connected to its people and its makers,” says the artist and curator Alia Zaal Lootah. “The early relationship between the rulers and the tradesmen through the ports of Dubai has grown organically over time and created this connection between the people and the government.” This relationship is at the core of the Dubai Collection, a unique initiative that sees local collectors loan their art to create the city’s first institutional collection of modern and contemporary art. “The Dubai Collection creates a collaboration between the state, the collectors, the artists and the public,” Lootah adds. “It’s a beautiful initiative.”

An Interview with Tagreed Darghouth

“We have to share the language that we own with others, and there must be something that the viewer should be highly interested in, because it’s a conversation at the end of the day”.

Expressionism and Engagement. Tagreed Darghouth, Ayman Baalbaki, and the Legacy of Marwan Kassab Bachi

The important Syrian artist Marwan Kassab Bachi (1934 - 2016) moved to Germany in 1957 and spent most of his life in Berlin, studying and then teaching at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste. Unlike many other Arab artists who studied abroad, his work involves a dialogue with the German Expressionist strand of modernism, rather than Cubism derived from Paris, or American forms of Hard-Edge Abstraction.

Memory, Traces & the Passage of Time

Sinuous tire trails cover the foreground of Ali Cherri’s (b. Beirut, 1976) Dust and Other Anxieties (2013). The image, from Abraham Karabajakian’s collection, presents a section of a road. Cherri’s perspective splits the image into three, with marked differences in color and texture. Closest to the viewer is a dark, tire-marked surface. Moving up the image, we notice a flatter, lighter stretch of ground. At the far back, the hazy sky descends onto sandy land; half-hidden by clouds of dust, the fuzzy outline of a monumental statue interrupts the otherwise featureless view.

Density and/or Lightness of Urban Life

Today, over half the world lives in and around a city. By 2045, it will be closer to 70% . As more and more people turn metropolitan, new patterns of urbanity are set to emerge. Creative, dense, contested—cities are alive. They are also hard to decipher, difficult to recuperate within an objective map or explain, minutely, from any singular spot. In this light, the urban artist occupies a special position. She is placed to engage the architectures of our habitations, drawing from the overwhelm of reality and postulating, through aesthetics, the implications of how we live now.

Objects of the Threshold - a liminal reflection

The construct liminal stems from the Latin nouns liminis (or limen) meaning threshold and transire (trans emphasizing the beyond) - to cross over to the other side. Liminality was first used by anthropologists Arnold Van Gennep and later Victor Turner during the 20th century to describe the different stages and the social roles of the rites of passage during rituals (such as marriage or coming-of-age ceremonies). Van Gennep and Turner’s contribution concerning liminality lies in their emphasis on the importance of embracing an in-between, ambiguous, or disorientated state. They argued that these transitional moments are vital for us to move forward as they influence our identity. Contemporary cultural theory, such as Homi Bhabha’s postcolonial perspective in the seminal work The Location of Culture (originally published in 1994), was later greatly influenced by these viewpoints. He defines the liminal as a transitory, mediate “third space of enunciation” that is characterized by uncertainty, hybridity, and potential for cultural change. Cultural liminality is experienced for example when an individual is caught between two cultures after being unsettled or displaced, such as an immigrant experiencing diaspora in a new culture after forcefully having to leave home.

The Desert Picturesque

When considering historical landscape paintings, depicting deserts, palm trees, camels, and large tents in the distance, one might understandably recall images associated with Orientalism. This artistic approach developed from European fascination with cultures and landscapes beyond their own - specifically, those situated to the east of Europe (arguably including northern parts of Africa) - often oversimplified into an imagined collective place known as the Orient. However, Abdulqader Al Rassam’s painting scene from Badia/Baghdad prompts the onlooker to interpret a Middle Eastern landscape that adheres to European landscape painting principles but is neither painted for the European viewer nor portrays the “Orient” as something alien.

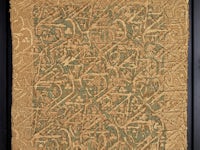

Hurufiyya and the Inspiration of Arabic Letters

The term Hurufiyya comes from huruf, the Arabic for ‘letters’, and refers to a form of painting that combines modernist abstraction with Arabic letters or calligraphy. It was coined by the Lebanese poet and critic Charbel Dagher in his book Huroofiya al-Arabiya: Fan Wa Hawiya (1991), translated into English as Arabic Hurufiyya: Art and Identity (2016).[1]

An Interview with Sarah Al Mehairi

“I think you should absolutely go for what you want to go for, explore themes and concepts that are maybe challenging.”

Dubai Calligraphy Biennale

Calligraphy—from the Greek for beautiful writing —is a form that elevates written language into an aesthetic experience. The medium, however, is more than simply pleasing to the eye. Calligraphy is a people’s expression of harmony, being “a statement about the sum total of [their] cultural and historical heritage.” In this spirit, the Dubai Calligraphy Biennale is a platform that gathers various calligraphic lineages. The event contextualizes penmanship as a carrier of history. The multilingual exhibits are an “opportunity for cultural exchange and understanding.”

The Diasporic Filipino Artist - Highlights from Filipino Artists in the Dubai Collection

What does it mean to be an artist in, or of, the Filipino diaspora? To live in the Filipino diaspora is to often be in search of rootedness. It is a constant questioning of your identity and how yours traces back to the motherland (or if it should). It is being in constant nostalgia, a perpetual desire to grasp on to something, anything, that will keep you tethered to where you came from.

Hala Khayat in Conversation with Emirati Artist Abdul Qader Al Rais

Time is not the true measure of a person’s success, but rather the achievements made. This is the case for Dubai based painter Abdul Qader Al Rais, who insists on his continuous support for the art scene in the United Arab Emirates. Today he is in the process of building up a studio space which will be also open to host younger Emirati artists he wishes to mentor. Garnering many regional and international awards over five decades of continuous and relentless work, today Al Rais has become one of the most acclaimed and iconic painters of the United Arab Emirates and a pioneer amongst his peers in creating a true distinct Emirati visual identity. With his unique style inspired by the region’s landscapes and the Arabian Desert architecture, his work is identified by lightness and speed.

For love or money: the art of collecting

“Buy what you love.” This catchphrase is often the first piece of advice given to anyone who suggests they want to purchase a work of art. It is usually followed by the equally confounding “don’t buy art to make money”. But how easy is it to get that right? To truly understand what it means when people say, “it should speak to you”? There’s no set criteria or qualifications to become an art collector or patron of the arts. You don’t need to attain a good degree from a top university or complete a foundation course at an arts college. Strong references or evidence of visiting leading museums around the world are not a prerequisite (although it all helps). It is not imperative to declare your financial status either (although efficient auction houses and galleries will do their research). In many ways, it is the most unfettered and liberating position to be in the art world – and the most essential. This is especially true in a new market such as the scene that has emerged in Dubai during the past two decades.

Painting Nothing: An Introduction to Abstract Art in the Middle East

The traditional Western art history books will tell you that the Russian artist Wassily Kandinsky “invented” abstract art—depiction free from representation, focussing instead on elements of form, colour, line, tone, and texture—in around 1910. As with much of the art history canon, this narrative is slowly being unravelled and lesser-known histories of abstraction are being added to the story, such as the contributions of female artists (for example, the Swedish artist Hilma af Klint painted her first abstract work in 1906) and artistic developments in non-Western regions.

Envisioning a New Collecting Institution in the 21st Century: The Beirut Museum of Art, Lebanon

What should a 21st Century museum look like on the inside? As the newly appointed Co-Directors of the Beirut Museum of Art, Juliana Khalaf and myself have almost a carte-blanche to reinvent what this means – an opportunity that comes once in a lifetime for art world professionals. The museum, which is slated to open in 2026, is the first purpose-built museum of its kind for Lebanon, promising to showcase the treasured art collection of the Lebanese Ministry of Culture (which has never been seen before), in addition to focusing on Modern and Contemporary regional art.

Insight: The Dubai Collection

The best examples of art begin conversations. A balance between commercial and didactic activity has always been a strength of Art Dubai’s programming. This is often the case in an emerging market, without established institutional models, and there is so much that has not yet been said–new voices to listen to, trends, movements, styles and influences to identify. It is why Art Dubai has cultivated a culture of discovery, and is a major catalyst in local, regional, and international artistic practice and creative ideologies. It has also consistently been a true connector–leaders and practitioners in the artworld from across continents and diverse art centres come together, often for the first time, and go on to establish impactful partnerships. It has been a unique model for nearly two decades, a space where commercial gallerists, collectors and institutional directors interact, where artists and curators feel at home. Art Dubai has also never only been about a few days in March but extends its reach throughout the year and across the globe.

Modern Iraq: The New Vision Group

A flurry of art groups blossomed in 20th-century Iraq. Following the formation of the country after the First World War and its independence from the British in 1932, a spirit of liberation rippled through the country: it was the dawn of a new age.

The Dubai Collection Announces 279 New Artworks From 19 New Patrons Including 88 Artworks From His Highness Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum

Including the new additions, 406 artworks are now available to view on The Dubai Collection Digital Museum, featuring modern and contemporary artworks by 84 new artists.

Iván Argote: Inspiring Critical Thinking Through Humour

LISTENING BEYOND AESTHETICS: Laurence Abu Hamdan’s Sonic World

Hazem Harb: Tracing Memory, Architecture, and the Politics of Space

Interview with Afra AlDhaheri

Conducted by Katarzyna (Kasia) Dzikowska on December 4, 2024

Hoda Tawakol: Interrogating Identity Through Explorations of In-Betweenness

Between Form and Subject: Exploring Nour Malas’ Artistic Practice

Style, Material, and Subject Matter in the Oeuvre of Chaouki Choukini

Art as a Tool for Advocacy: Aïda Muluneh’s Water Life Series

Exploring Performance as a Tool of Creation in the Work of Maitha Abdalla

In Conversation with Alia Hussain Lootah

Missak Terzian in conversation with Hala Khayat

Mystical African Abstractions: The Pioneers of Sudanese Modern Art

The avant-garde works of Sudanese artists, such as Ibrahim El-Sahali and Kamala Ibrahim, reveal gems of abstract art hailing from East Africa

In Conversation with Dana Awartani

Evoking the Beauty, Perseverance and Resistance of Palestine: Sliman Mansour

Millions of Pieces and Stories from West Africa: The Art of El Anatsui

Artist profile: Huguette Caland

“I love every minute of my life. . . I squeeze it like an orange, and I eat the peel, because I don’t want to miss a thing.” Such free-spirited words were once spoken by the celebrated Lebanese artist Huguette Caland, who died in 2019 at the age of 88. The unconventional Caland, who was also a sculptor and designer with a career lasting for five decades, pushed boundaries with her sensual paintings and personal choices, living life to the fullest.

Marwan Kassab Bachi and German Expressionism

Marwan Kassab Bachi (1934 - 2016), one of the most acclaimed of Arab artists, moved to Germany from his native Damascus in 1957 and studied painting for 6 years at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste in what was then West Berlin. He went on to teach there until 2000, and he spent most of his life in Germany. In the painting classes of Hann Trier at the Berlin academy, he met Georg Baselitz (born 1938), who from the late 1970s onwards became one of the most celebrated and controversial German painters.

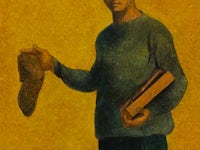

Artist Profile: Louay Kayyali

When one thinks of modern Syrian art, a name that often crops up is that of Louay Kayyali. A twentieth century luminary, Kayyali is loved for his gentle portraits of the everyday man, woman and child. He was born in Syria's largest city, Aleppo, in 1934, an important year in world history: Adolf Hitler declared himself 'Führer' (or leader) of Germany, Russian astronaut Yuri Gagarin was born, and renowned physicist Marie Curie died. What lies beneath Kayyali's quiet imagery, noted for depicted struggles of the masses, is a short life marred with personal tragedy.

Artist Profile: Maha Malluh

Maha Malluh’s work engages with important global issues of consumerism, memory, gender, and rapid social change, but her work is also strongly rooted within Saudi culture and history. She is an international artist, but has said that her country is the primary inspiration for her work. [1] Like all good art, her work provokes surprise. It forces us to look more closely, and to make connections that we probably wouldn’t have made otherwise. She has worked in a range of media, but is perhaps best known for her artworks which blur the distinction between the two-dimensional and the three-dimensional.

Artist Profile: Manal Al Dowayan

Manal Al Dowayan addresses issues of identity, culture, and gender. She is perhaps best known for her artworks relating to the legal and social status of Saudi women, although her more recent work has moved to a focus on the narratives of Saudi history.

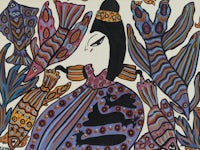

Seeing Otherwise, The Eye as an Icon in the Art of Baya Mahieddine and Alymamah Rashed

The Idea of Landscape

What Ruin Can Mean

Feminist Materialities in the Work of Three MENA Artists

From Sustenance to Signifier. Food in Contemporary MENA Art.

Techniques of the Body

The Museum as Method

Across Four Cities: Rethinking Modernist Art in the SWANA Region

Objects, Domestic and Everyday

Institutions without Curators: Finding New Perspectives

Modularity and Modulation: On the Subtle Art of Sarah Almehairi

Helen Khal: Luminous Abstraction and the Feminine Voice in Arab Modernism (1923-2009)

Hamed Abdalla: The Revolutionary Letterist of Modern Arab Art

Truth In Memory: A critical commentary on the juxtaposition of memory and truth in the context of four artists from The Dubai Collection

Untold Stories: Exploring the Use of Narrative in the Work of Aya Haidar

Art Spaces not IRL: The Rise of Digital Museums

Art Spaces without Storage: The contemporary burden of “stuff”

New Ways of Artmaking: Contemporary Art after the 1979 Iranian Revolution

Artistic Mission: The Role of Pioneering Arab Women Artists in Modern Arab Art

Female Arab artists of the 20th century are coming into their own for their indelible contribution to the history of Modern Arab art

The Bride (Undated) and Motherhood (1987)

“I was born in a very modest place, therefore, I paint children, mothers, families, I paint misery, birth, death, and I paint the noise. I paint the tight-knotted groups that are lost, scarred, expelled, not knowing where is their next destination, I paint the neighborhoods which witnessed war, and hunger. Fear, genocide, siege, illness and death, from all of these ingredients I explode and I paint”. Paul Guiragossian, 1984 [1]

Gathering the Land’s Stories: The Living Symbolism of Olive Pickers (2013)

Reverberations of Memory: The Resonant Power of Chant Avedissian’s Om Al Soubain, Icons of the Nile 1971 (1991)

Rhythms of Return: Samia Halaby’s Landscape (2009)

A Lyrical Meditation on Memory and Renewal: Kamrooz Aram’s Backdrop for a Seasonal Revelation (Palimpsest #19) (2013)

I Saved My Belly Dancer

Between Fragments: Huda Lutfi’s Togetherness (2005)

From Places (2021) Mapping Memory, Color, and Belonging

Morning (2018), A Modern Impressionist Reflection on Nostalgia

Etel Adnan: A Final Testament to Color, Conflict, and Cosmic Witness

Suad Al-Attar’s Testament to Loss and Endurance

Ribal Molaeb: A sensory, symphonic experience of visual harmony.

Tree (Undated, late 20th Century) Windows of light and the emotive vocabulary of color.

Jamil Molaeb: Arbre aux oisseaux [Bird Tree)] (undated) A haunting visual metaphor of constraint and liberation.

Seher Shah: Of Absence

Harmony and Experimentation. Two Paintings by Mouteea Murad in the Dubai Collection.

Marwan Chamaa: La Dolce Overdose (2012)

Assadour’s Clockwork Orange

An Exploration of Timo Nasseri’s Artistic Practice Through His Work I Saw a Broken Labyrinth #14

Juma Al Haj, Of Mud, 2021

Mohammed Kazem and Conceptual Art in the UAE. Conversations from June 2024

The Collector Series: The Habbal Collection

Reem El Roubi and Amir Daoud Abdellatif Collection

In Conversation with Nadine Kanso

Kampala-Baku

Both Kampala and Baku had dynamic art scenes between the 1960s and 1980s. Linking these two cities—and more generally, East Europe and East Africa—are the many art students and intellectuals who worked across these regions, absorbing and translating images, objects, and sounds from one context to another. This conversation brings these historical and present-day art worlds into focus, with experts who can speak to the challenges and opportunities of recovering lost histories and working in today’s global art market.

Cairo-Moscow

This talk shifts attention from Western institutions and their influence on modern art in the Arab World, focusing instead on overlooked yet impactful artistic and political connections between this culturally diverse region and the Soviet Union.

Almaty-Colombo

Though Central Asia and South Asia may seem to exist in different cultural and geographical hemispheres, artists working in these regions also had shared experiences in the late twentieth century: the rise of nationalisms, civil unrest, an interest in recovering native languages and art practices, and a desire to connect with a nascent global art world. For this talk, specialists in art from Central Asia and South Asia come together to highlight these parallel histories.

Collecting Beyond Borders: Dynamics and Diversity in Art Collection Practices Across the Global South

The talk uncovers the multifaceted stories of collectors who navigate the intersection of local and global, grappling with questions of identity, representation and cultural heritage – shining a light on diverse voices that make up the global artistic landscape. This conversation also examines the role these collectors play in shaping the perception of art from emerging cultural epicentres on the international stage.

Beyond the Private Vault: The Evolution of Collecting

The conversation unpacks the trajectory from private collecting towards institutional legacy in the Middle East and South Asia with patrons who have established their mark in private collecting and shifted their focus towards institution building. This panel aims to address the arising question: what happens to personal collecting efforts in light of this focus shift, in geographical regions where there is still more room for both?

Harmony in Patronage: Nurturing Art Ecosystems

An exploration into the intricate relationships between arts patrons and arts organisations that delves into the crucial role these patrons play in sustaining and enriching vibrant ecosystems of artistic expression. Examining how collaboration helps establish support systems for the production and dissemination of art, and drawing on contemporary case studies, this conversation uncovers the various dimensions of these dynamic partnerships from a regional perspective.

The Art of Collecting

This panel brought together a group of collectors with varying disciplines at different stages of their collecting journey, who shared insight about their practice. They shed light on the increasingly important role collectors play, and how they set their strategy and focus their patronage.

The Future of Institutional Collections: Perspectives From The Region

This conversation explored the process of developing new models for building publicly accessible art collections, where representatives from different institutions in the region discussed policy and curatorial concerns specific to their context.

Geographies of Land and Faces in MARWAN's World: Their Deconstruction & Reanimation

Pioneering artist MARWAN Kassab Bachi left his mark on the contemporary art scene, with his work celebrated in both Eastern and Western contexts. He influenced an entire generation of young artists, and this panel reflected on a lifetime of stories, friendships, inspirations, and the rich body of work that makes up his legacy.

Modern Art and Museums

The conversation reflected on possible ways to include and present modern art from MENASA countries in international museums and how to preserve the region’s heritage in the light of global market interest.

Are You Still Collecting Crypto In The Digital Winter?

What does it mean to be a collector of digital art today? In what is being dubbed as the ‘crypto winter’, the panelists discussed if it still makes sense to acquire digital works. Collectors Qinwen Wang and Fiorenzo Manganiello talked about where digital art sits during such a precarious time, the history of digital art (delineating digital art and NFTs), and their own involvement with it.

Abstraction and Figuration: Looking to Shapes

By critically reviewing the history of pictorial abstraction around the middle of the 20th century, the conversation reflected on the canons of artistic modernity by creating a bridge between past and present and reconsidering the theme of figuration in the light of experiences in the MENASA countries.

Luxury Retail and Art

As the world of art broadens its borders, luxury retail and art collaborations have been a natural outcome. This panel brought together leading representatives across the luxury retail and art worlds to discuss their involvement with the arts, how their affiliations and practices incorporate art, and the role that plays in the DNA of the organisations they represent.

Building a Collecting Community

This panel brought together UAE-based collectors to discuss their collecting journeys and practices over the years, how those have shifted in light of a growing cultural infrastructure, and the role they play in building collecting communities.

From Collector To Patron: Supporting Artistic Production In The Region and Beyond

This conversation explored forms of art patronage that support new media art and in specific video art, particularly in/for a region implementing new institutional models and cultural infrastructure. The talk highlighted new initiatives and patronage efforts with collectors engaged in impactful art endeavours, with a focus on the role of commissioning private institutions in supporting the production and exhibition of digital and video art. The conversation brought together Han Nefkens, collector and founder of the Han Nefkens Foundation, which supports emerging international video artists through awards, production grants and mentorship grants, and Antonia Carver, director of Art Jameel.

Collecting In A Shifting Global Cultural Map

The role collecting and collectors are playing in shifting arts and culture landscapes, as well as in the redistribution of global cultural centres. This panel brought light on new collecting emerging in the Global South, the impact these new collectors had on the cities/geographies they’re based in, and the effect of these practices in the larger global conversation around diversity and inclusion of art from beyond traditional western-led geographical scopes.

On Creating: Maitha Abdalla

On Creating: Nima Nabavi

We met up with Nima Nabavi to discuss what creating means to him. He told us about his grandfather’s influence on his practice, how growing up in 80s Dubai transformed the way he understands aesthetics, and the puzzle of sacred geometries found in nature. Nima Nabavi is a self-taught artist based between Dubai and New York. His practice centers on geometric abstraction and its connection to the natural world and quantum processes. Drawing on an ever-expanding set of tools, ranging from the traditional to the technological, Nabavi creates grid-based compositions of elaborately layered, imagined ordered forms. His mathematical approach and repetitive numeric symbolism rely heavily on advanced planning, precise calculations, and self-developed methodologies to ensure the vital structural accuracy of each work.

On Creating: Tagreed Darghouth

On Creating: Juma Al Haj

We visited Juma Al Haj's studio in Sharjah to discuss what creating means to him. He shared the meaning of religious texts with us and how they impact his work, from language to design, the importance of finding inspiration outside of one’s practice, and how his experiences abroad have shaped his identity.